Television and I grew up together. This is our story. Third in a series.

They weren’t the scripted dramas or comedies—which were normally done by actors standing in front of microphones, with somebody off to the side doing sound effects to simulate the action. But there were also radio shows that were essentially live stage shows, performed before audiences (soon to be known as "the studio audience.") These were the easiest to adapt to TV. So two of the biggest stars in early TV were two popular hosts of radio shows, doing basically the same shows on television.

Arthur Godfrey was a former local radio announcer who hosted the first successful quiz show on radio in 1937, Professor Quiz. He became famous for his live coverage on CBS radio of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s state funeral in 1945, a very emotional moment for the country that had depended on FDR for more than 12 years, through the Great Depression and World War II.In 1945 Godfrey began his own program on CBS Radio called Arthur Godfrey Time. It ran for an hour and a half every weekday morning. It was part talk, part monologue, part entertainment with skits, singers and a live band. Godfrey often improvised, suddenly breaking into song he accompanied on his ukelele, with the band trained to follow.

In 1946 Godfrey also began hosting the weekly Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts on CBS radio. It became one of the first programs to be simultaneously broadcast on television in 1948, every Monday evening. Professional entertainers vied for their big break, including Tony Bennett, Marilyn Horne, Patsy Cline and Lenny Bruce. It was the country’s most popular TV show in 1951-2, and remained in the top ten for most of its decade on TV.

|

| Julius LaRosa with Godfrey |

Godfrey became controversial, both for his liberal (against racism, for the environment) and conservative politics, and his off-camera tyranny. He was famous for firing singer Julius La Rosa on the air for no apparent reason, though it wasn’t on television as often claimed—it was during the radio-only portion of his morning show. The contrast between his folksy friendliness on air and his backstage behavior allegedly inspired A Face in the Crowd, the classic film starring Andy Griffith.

Another famous early TV figure who moved his operations from radio was Art Linkletter. He was a radio success in the 1940s with his shows People Are Funny and Art Linkletter’s House Party. He got his television feet wet in 1950 with the fledgling ABC network’s Life With Linkletter, and a fifteen minute program interviewing children that was mostly a local New York show. These interviews were also a regular segment of his House Party radio show, which itself was added to CBS network television in 1952, when the ABC series ended. It incorporated the kids segment, which became the basis for Linkletter’s best-selling books, Kids Say the Darndest Things.)People Are Funny was an audience participation show that moved to television in 1954. One show I recall featured a man who would win a large cash prize if he could go a week without breaking any laws. He was so careful that week, Linkletter noted, that when he opened a pack of cigarettes he didn’t tear the official stamp on the top of the pack. That’s when we all learned that not tearing the stamp was illegal. For some reason.

Godfrey and Linkletter were comfortable performing live—another reason they were successful on television. That was also the advantage of stage performers—nightclub singers, vaudeville comics, jugglers and puppet shows. Even radio actors and announcers, unlike movie actors, were used to performing at the same time the audience experienced their performance.Live performers were often needed even when early TV did run those old movies, movie serials and cartoons. A live host or act that attracted an audience would introduce them, and more importantly, plug the sponsor. This was especially true when the audience was primarily composed of children.

(There is one notable exception to the “live” part. Captain Midnight was a well-known radio hero, but his first appearance on TV was a short piece of film that introduced every Saturday’s half hour of Zorro and other old movie serials—claiming they were adventures of Secret Squadron members-- as well as shilling for Ovaltine. Eventually Captain Midnight made the full transition to a dramatic TV show.)

Most of the programs built around showing truncated old movies, serials, old cartoons and repackaged shorts like the Old Gang comedies that became the Little (or L'll) Rascals on TV, were created at local stations.

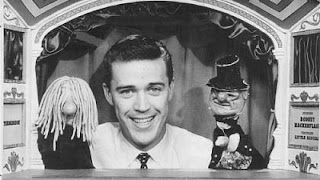

|

| Knish, Stohl, Rodney |

(A subsequent Pittsburgh show in the late 50s, “Adventure Time” with host Paul Shannon interacting with a studio audience of schoolkids, began showing old Three Stooges comedies to such acclaim that their careers were revived.)

But the Pittsburgh puppets were going along a road already established in Chicago by puppeteer Bert Tillstrom and what eventually became known as Kukla, Fran and Ollie. Tillstrom started developing his repertory company of puppet characters during the Depression through the Federal Theatre Project, and became so successful that his troupe (the Kuklapolitans) appeared at the New York Worlds Fair in 1940.

In 1947, he got a weekday TV show on a local Chicago station. To his puppet characters like Kukla and Ollie (the one-toothed dragon), he added a human interlocutor, singer Fran Allison. To fill the hour, they introduced cartoons and movies, but their improvised conversations and situations became the program’s chief draw.It would be awhile before TV networks became truly national, but Kukla, Fran and Ollie became the first TV show originating in Chicago to be hooked up to the East coast and cities in between, via NBC’s new coaxial cable in 1949. Its format and broadcast time changed over the years, so I remember watching it when I could. Its gentle wit also made it a hit with discerning adults.

Also in the late 1940s, the New York-based Howdy Doody Show developed from a circus premise, a few characters and old comedy shorts to a more elaborate world of Doodyville and numerous characters. In its heyday of the early to mid 1950s, the show’s originator and host Buffalo Bob Smith interacted with marionette characters ranging from the old fussbudget Mayor and Howdy nemesis, Phineas T. (Mr.) Bluster, to Dilly Dally and Flub-a-Dub, as well as human characters Clarabell the clown, Chief Thunderthud and the Indian maiden, Princess Summerfall Winterspring.

|

| Flub-a-Dub and Dilly Dally |

Howdy Doody was another major hit of early television. I was a faithful viewer at 5:30 pm every weekday. In the early fifties, it was the first show of the day on NBC, and might be preceded by a test pattern, then another with Howdy’s face in the middle.

The ancient form of the puppet show was only one Howdy Doody source. True to its origins, the circus was another, especially clowning. Yet another was vaudeville, with its song and dance, sketches, slapstick and other comic bits. The mixture was even more evident in contemporary imitators like the Pinky Lee show. Howdy Doody was also another wellspring of products, and I’m pretty sure my first phonograph was a Phono-Doodle.

It debuted in 1949 as a 30 minute show several times a week. A pretty close knockoff of Captain Midnight crossed with Edmund Hamilton’s print-only Captain Future, Captain Video was originally designed to fulfill the same function as the first TV Captain Midnight did later: basically introduce film footage. At different points in this show’s history, that did become part of it—in the guise of adventures of distant Video Rangers, excerpts from old westerns would fill the screen.

But even as the show was being conceived, the idea grew that actors could enact dramatic adventures as most or all of the show. By the time I recall regularly watching it, Captain Video and His Video Rangers was a fifteen minute show with nothing else added, broadcast every weekday at 7 p.m. Like just about everything else in 1953, it was done live.

To the stirring strains of Wagner's Overture to "The Flying Dutchman," the announcer intoned: "POST--the cereals you like the most...take you to the secret mountain retreat of Captain Video! Master of Space! Hero of Science! Captain of the Video Rangers! Operating from his secret mountain headquarters on the planet Earth, Captain Video rallies men of good will and leads them against the forces of evil everywhere! As he rockets from planet to planet, let us follow the champion of justice, truth and freedom throughout the universe! Stand by for...Captain Video...and his Video Rangers!

By then, Captain Video had evolved from an earthbound scientist and inventor to an interplanetary adventurer in the year 2254. His spaceship, the Galaxy, was the first ever on a television show.I stared at that robot, alert to any tiny signs of movement while characters chattered on, for what seemed like an infinite series of episodes. (The show sometimes moved at the pace of a soap opera.) Then of course I missed the episode when Tobor actually came alive. When I caught up with the story, he was already in space, menacing the Galaxy. Tobor figured in subsequent story lines, eventually as a good guy hero.

As a Dumont show, Captain Video’s budget was tiny, mostly poured into its few and often repeated spaceship special effects. There were cardboard sets and lots of flubbed lines. We didn’t notice. The show generated premiums and other merchandise for its young audience, but adults also watched it. The writers who contributed to Captain Video reads like pages from a Who’s Who of 1950s science fiction. They included Issac Asimov, Arthur C. Clark, James Blish, Damon Knight, Milton Lesser, Walter Miller, Jr. (author of the classic A Canticle for Leibowitz) and Cyril M. Kornbluth. They seeded the stories with some actual science, as well as messages of fairness, tolerance, equality and democracy. Captain Video was even seen negotiating an interplanetary peace.Captain Video had a family audience, but its popularity with kids is suggested by this recollection: one day in grade school we had a young substitute teacher who brought in a phonograph, and said she would play something, and we should all draw what we thought of as we listened. There was a titter in the class when we heard the first strains of the Flying Dutchman theme, which the teacher obviously didn’t relate to Captain Video—until she got back a lot of drawings featuring robots and space ships.

The success of Captain Video suggested another area of storytelling beyond the western with both kid and family appeal. Soon there were other captains and commanders and other heroes rocketing across our screens, in particular joining the TV menagerie defining a new kid TV zone... So stay tuned for our next exciting episode: Saturday Mornings in Outer Space!